SELECTED PRESS

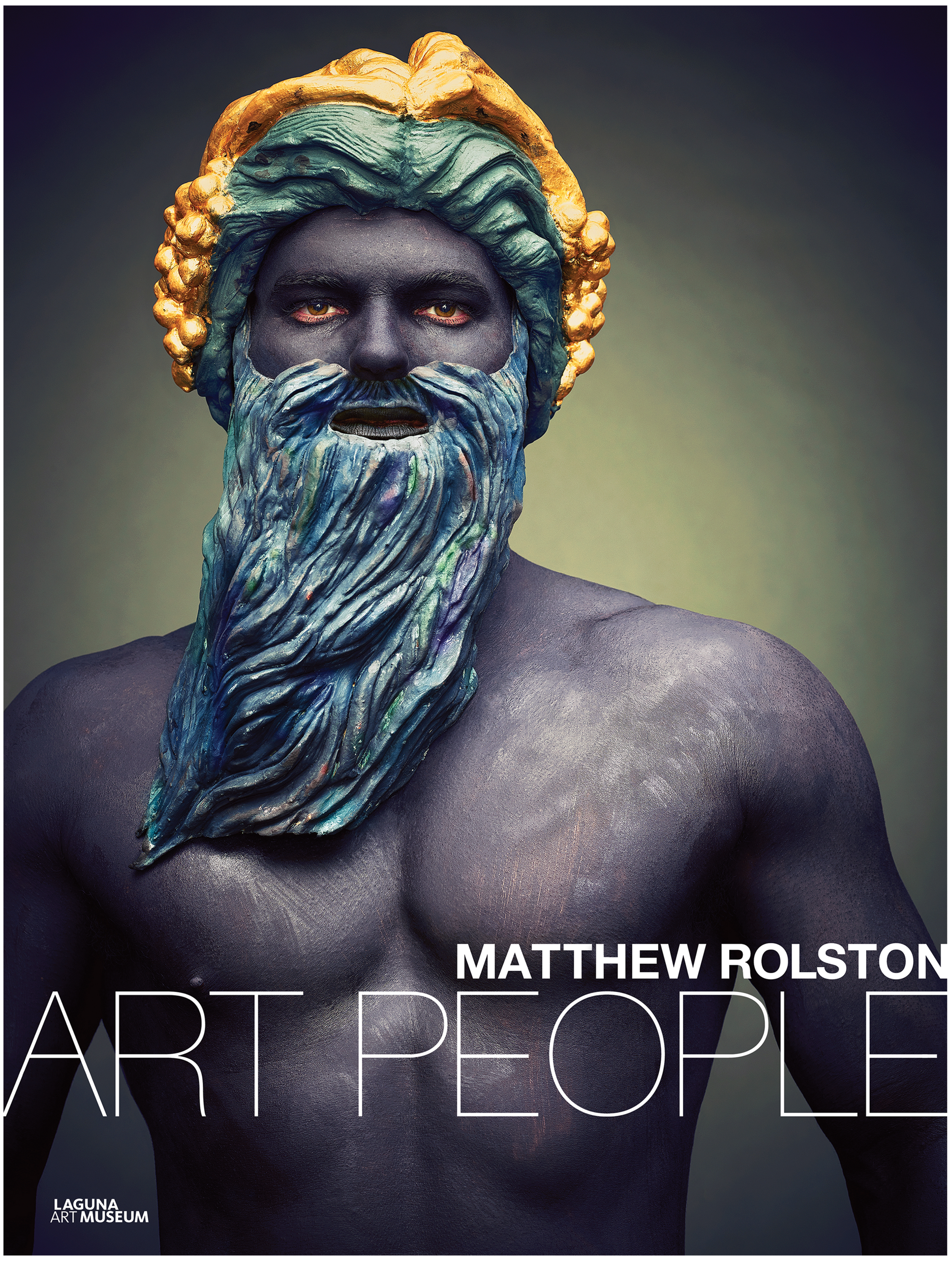

The Magic of Painted Bodies

MATTHEW ROLSTON’S PAGEANT OF THE MASTERS PORTRAITS ARE WONDERS ALL THEIR OWN.

By Christopher Knight

When supervillain Auric Goldfinger ordered glamorous card-shark Jill Masterson to be painted head to toe in his favorite gilded hue then deposited in James Bond’s rumpled bed in 1964’s superlative 007 movie, murder and intimidation were the aim. The paint was claimed, fictionally, to have caused the beauty’s death by skin asphyxiation.

Painted bodies don’t have the same nefarious result at the Pageant of the Masters. Maybe that’s because makeup rather than polyurethane acrylic does the annual job at the famous Laguna Beach summer festival of tableaux vivant. For the 2016 edition, however, a gilded lady was again the victim of barbarians — this time from the epic Ludovico Ariosto poem “Orlando Furioso,” fan-favorite during the Italian Renaissance

The lovely Angelica — stripped naked, chained to a rock for the dining delight of a giant sea monster and daringly rescued by Roger, a valiant knight — was also a popular subject in 19th century France. During a floundering epoch of post-revolutionary destabilization, the French were mad for organizing guidelines drawn from history and myth.

The Pageant chose Angelica’s florid representation from an 1840s bronze by sculptor Antoine-Louis Barye. She escapes across the sea in Roger’s protective arms, riding on the back of a galloping winged-horse held aloft by a coiling dolphin.

Celebrity photographer Matthew Rolston, known for lush portraits of actors and musicians, took a different approach in “Art People,” his exhibition of 2016 Pageant photographs currently at the Laguna Art Museum. Cinematic melodrama and sculptural romanticism are nowhere to be seen in his picture of Barye’s maiden.

“What’s oddly compelling is that the photograph undercuts any expectation of personal exposure, which is what we normally expect a portrait to accomplish.”

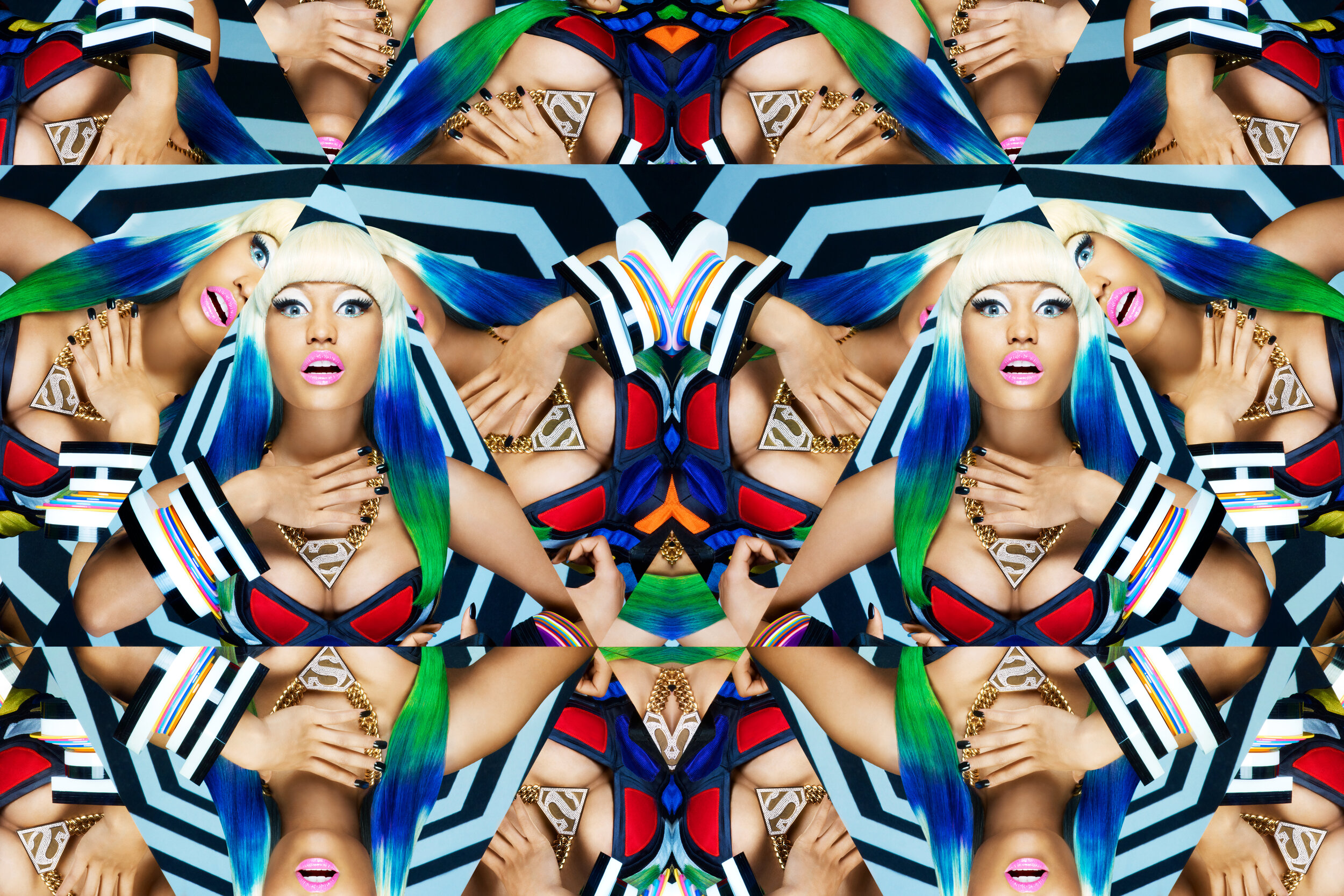

Instead, “Art People” turns the same demanding techniques of studio work applied to publicity shots of Nicki Minaj and Zac Efron and for the pages of Rolling Stone and Vogue to anonymous Laguna locals who portray characters from paintings and sculptures. The results are agreeably weird.

Rolston’s gilded Angelica faces forward, body turned to three-quarter view and cropped just above the knee. Every inch of exposed skin is shiny gold, except for the rims of her eyelids. So is her draped tunic and the hard, coifed cap that substitutes for soft hair, like an ice-cream cone dipped in chocolate. The blue eyes and white front teeth on a sober, unsmiling face are of course unpainted, the lone suggestions of a living, breathing human being trapped inside.

The portrait could not be more formal. What’s oddly compelling is that the photograph undercuts any expectation of personal exposure, which is what we normally expect a portrait to accomplish. Rolston posed the model, one arm hidden behind her, with her right arm slightly bent and her hand turned to an open palm — a gesture of candidness that quietly resounds against her actual concealment.

Here I am. Who am I?

This is a person, identity unknown, portraying an object for a tableau presented in a theater. The show is the thing. The individual woman you’re looking it remains a cryptic cipher, encased inside layers of artistic and cultural distancing. Who she is really doesn’t matter.

“Rolston’s exquisitely crafted pageant pictures are all mask. Some are spectacular - especially the crowned and bearded figure of Neptune, Roman god of the sea.”

When you look at Antoine-Louis Barye’s bronze sculpture in an art museum, rarely does the mind turn to the question of who the model was working in the artist’s studio posing for Angelica in the wax or plaster form that would later be cast in enduring metal. Her life was lived, and that was that. The sculpture, which is not a portrait, lives on.

“Art People” is a strange inversion of celebrity photography, in which we casually assume we are seeing behind the public mask of a famous performer. Rolston’s exquisitely crafted pageant pictures are all mask. Some are spectacular — especially the crowned and bearded figure of Neptune, Roman god of the sea.

Plucked from the base of a ponderous fountain in Paris’ Place de la Concorde, he’s a cast- iron spectacle with an odd cap of gilded foam. A windswept blue beard is clamped against his face, his muscled, purplish torso streaked with brush marks. The model is buff but nowhere near as bulky as the actual laborious statue designed by German-born French architect Jacques Ignace Hittorff. He’s hardly a household name today, but Rolston’s photographic fountain god elicits double-takes.

“The inspiring and the prosaic collide, the sacred indistinguishable from the profane. Leonardo’s actual fresco recedes into the conceptual distance. Rolston’s photographs assume a life of their own. ”

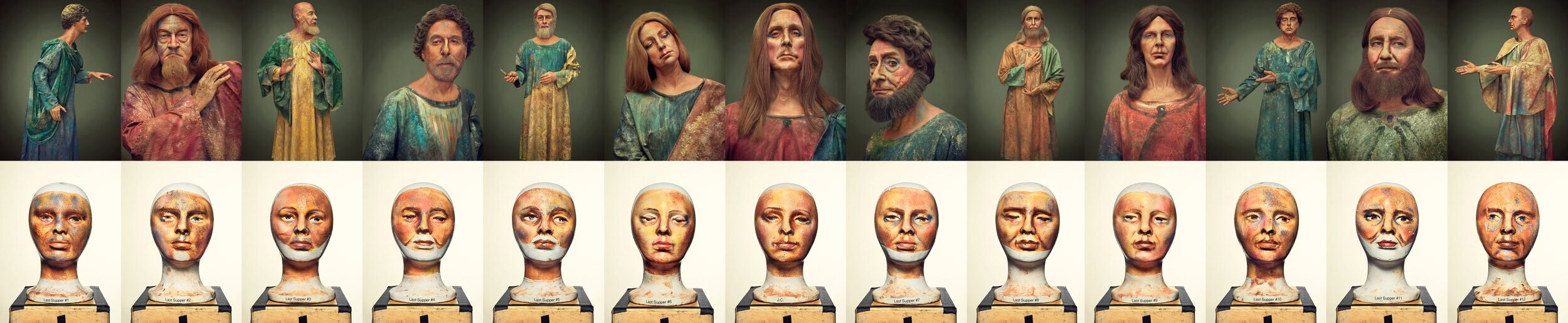

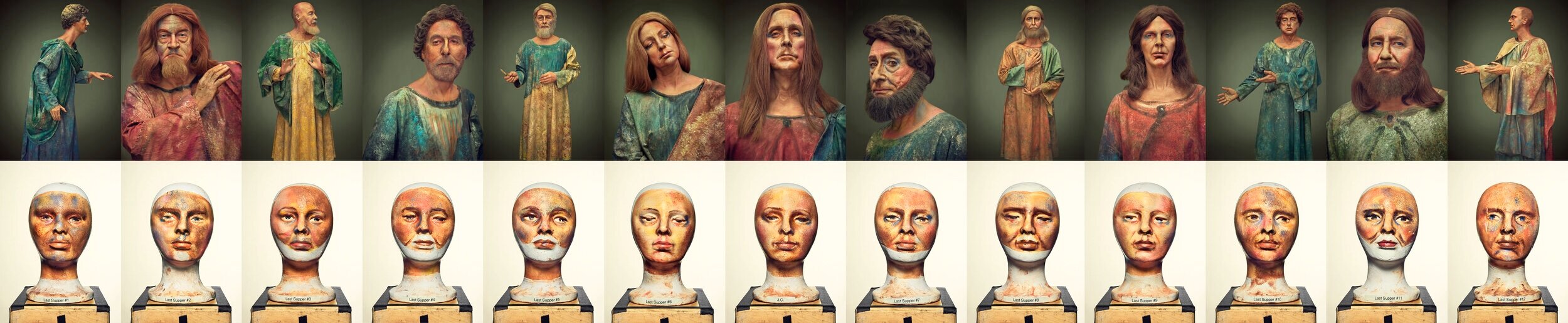

Others seem disconcertingly tatty — none more than the 13 characters in Leonardo da Vinci’s “The Last Supper,” annually the pageant’s grand finale. Christ and his disciples, robed and bewigged, are here a rather creepy and forbidding bunch, the makeup so pronounced that it’s sometimes hard to tell the costumed sitter’s gender.

Their beards are like scrubbing brushes, their stiff, paint-daubed tunics like housepainters’ drop cloths. Absent context, hand gestures perform a supercilious pantomime.

The inspiring and the prosaic collide, the sacred indistinguishable from the profane. Leonardo’s actual fresco recedes into the conceptual distance. Rolston’s photographs assume a life of their own.

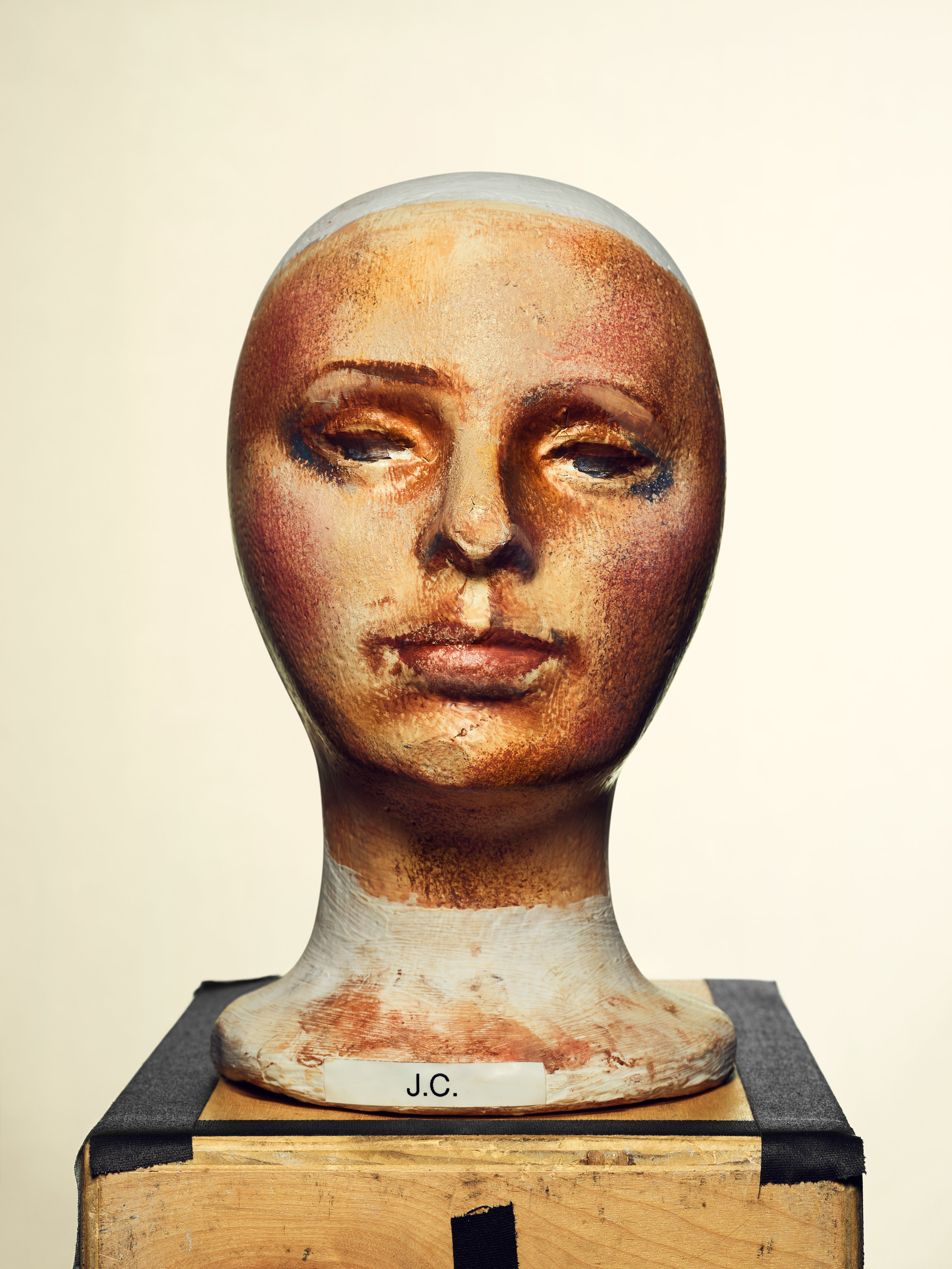

One coincidentally revealing example is the 1966 portrait of the late Los Angeles art dealer Nicholas Wilder, painted shoulder-deep in his home’s oval swimming pool by David Hockney. Rolston presents him in two adjacent photographs — one the painted plaster bust that pageant designers use to guide the nightly ritual of preparing the cast member for the show, the other the performer ready to go.

I knew Wilder, who ran one of Los Angeles’ most important art galleries for 14 formative years in the city’s contemporary cultural life. Looking at the technically refined, high- resolution photographs of both mannequin and model, I was surprised at how little either one resembled him. Like the Hittorff Neptune and Leonardo’s Jesus, being in the artistic ballpark is close enough for the pageant.

After all, close scrutiny of a painting or a sculpture is not the aim of a tableau vivant. I’ve long thought of the Pageant of the Masters as being somewhat akin to a sporting event, where extensive training, precision workouts and repetitive practice lead to the starting- gun moment when the curtain opens and, in a reversal of many sporting norms, the “art athletes” must remain perfectly still for the duration of the exposure.

If that sounds like the way photographs were made during the camera’s 19th century infancy — well, it’s not coincidental that the tableau vivant was birthed and flourished around the same time. It isn’t exactly a democratizing impulse for art, but taking pictures and making them were entering a new historical phase. Rolston’s peculiar pageant pictures begin to bring the world-altering saga into unexpected focus.

The Art of Matthew Rolston

By Tom Teicholz

Matthew Rolston’s exhibition “Art People: The Pageant Portraits” at the Laguna Art Museum is a show as beautiful, as mysterious, as life-affirming, and as much about human creativity and art as Pageant of the Masters itself. And in a sense, it is also a metaphor for the career and work of Matthew Rolston himself.

At several exhibition-related artist talks by Rolston that I attended recently, including one where Rolston was in conversation with Los Angeles-based journalist and editor Merle Ginsberg at the Britely Social Club at the Pendry Hotel in West Hollywood, and another at the Laguna Art Museum where author and noted culture writer Christina Binkley was his interlocutor, Rolston discussed both his career and early influences.

“Matthew Rolston’s exhibition Art People: The Pageant Portraits at the Laguna Art Museum is a show as beautiful, as mysterious, as life-affirming, and as much about human creativity and art as Pageant of the Masters itself.”

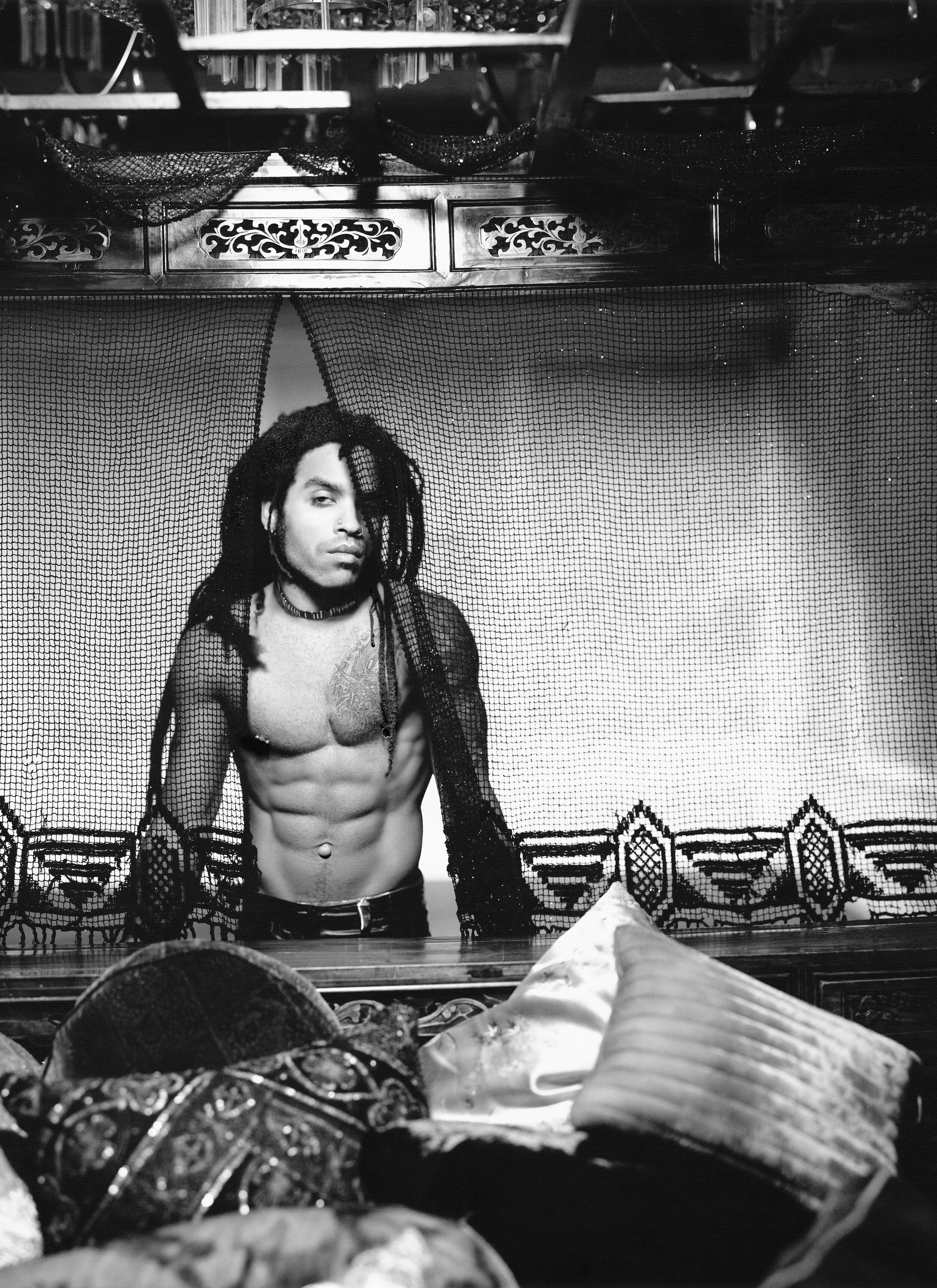

Rolston grew up in Los Angeles and attended pretty much every art school in the area, including Chouinard (the forerunner to CalArts), Otis, and ArtCenter in Pasadena. He became enamored of golden-age Hollywood studio portraits that he found among the memorabilia and collectors’ stores on Hollywood Boulevard. At an early age, his career was launched when he got an assignment to shoot Steven Spielberg for Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine.

Rolston was fortunate in finding an early home at Interview, as fortunate as Interview was to discover Rolston. Back then, in the days when Warhol himself was very much a presence at the magazine, Interview was published as an oversize large format newsprint monthly, with cover portraits of celebrities stylized and colorized by Richard Bernstein – very much in a Warhol-esque color/block style.

Inside were short features and longer Q&As with celebrities and other notables, done in a manner that was meant to convey an actual conversation you were eavesdropping on, rather than a 60 Minutes Mike Wallace grilling. Due to Interview’s large format, the portraits accompanying the text were also super-sized and often in black & white (a money-saving strategy that became an editorial point-of-view). In the late 1970s and early 1980s, most mainstream magazine photography was focused on a casual hyper-realism – stars in jeans and white t-shirts, or stylized “real” portraits such as Avedon’s “In the American West” series of coal miners and others that conveyed a hard-won beauty.

Interview tacked in a different direction – a post-modern return to Hollywood glamour. Rolston’s portraits were the opposite of casual: they were highly staged, with great attention to lighting, every element thought out, with specific references to classic images of stars such as Garbo or Dietrich, and no detail too small to be unimportant.

From Interview, Rolston’s career exploded, doing work for magazines such as Rolling Stone (he’s shot more than 100 covers), Vogue, W, Vanity Fair, Harper’s Bazaar, The New York Times Magazine and O, the Oprah Magazine (he has shot Oprah for more than 40 magazine covers, more than any other photographer). There’s a sense of fun to many of his portraits, even a winking nod at the past.

Rolston went on to make films and music videos, including for Madonna, Jewel, Janet Jackson, Christina Aguilera, Foo Fighters, Beyoncé, Seal, and Miley Cyrus as well as advertising campaigns for brands such as Estée Lauder, L’Oréal, GAP (his Khakis Swing video is particularly memorable), Revlon, Polo Ralph Lauren and Burberry, among others.

“Having reached the summit of so many facets of his professional career, several years ago Rolston decided to embark on a series of non-commissioned art projects, series that he conceptualizes and executes at his own cost, spending at times years on the works. ”

Beyond his photo, film and video work, Rolston has also served as creative director on hospitality projects for clubs, restaurants, and hotels (such as the Redbury Hotels), bringing his attention to detail, style and flair to every element from marketing campaigns to staff uniforms.

Having reached the summit of so many facets of his professional career, several years ago Rolston decided to embark on a series of non-commissioned art projects, series that he conceptualizes and executes at his own initiative and own cost, spending at times years on the works.

“Rolston has said that his photos of the dummies were, on one level, an investigation of what makes us human. Which is interesting when you consider no humans appear in the series.”

Rolston found inspiration for his first fine art project “Talking Heads: The Vent Haven Portraits” in a museum of ventriloquist dummies, the Vent Haven Museum in Fort Mitchell, Kentucky. Rolston set up a portrait studio in the museum and photographed each of his subjects in an identical manner: square format, low angle, monochromatic backdrop, and a single light source. The square format recalls Warhol’s Polaroids, and the white backgrounds, Avedon’s late work.

Rolston has said that his photos of the dummies were, on one level, an investigation of what makes us human. Which is interesting when you consider no humans appear in the series.

Art People: The Pageant Portraits, Rolston’s second fine art project, currently on view in Laguna (with a beautiful catalogue available from the museum or the project’s own website) consists of portraits of performers taken during the 2016 Pageant of the Masters.

The Pageant is a 90-minute outdoor performance of a series of “tableaux vivants” or “living pictures” in which volunteers are costumed, made-up and inserted into stage sets that, when framed and lit, reproduce well known art works for an audience of some 2600 attendees every night from the 4th of July weekend to Labor Day, every year since 1933 (except for 1942-1945 during WWII and 2020 due to the pandemic). There is narration and although at times the figures move and even dance, the performers are neither actors nor dancers. They are more akin to re-enactors. It is a most unique, uncanny performance and a memorable experience.

Rolston attended the pageant as a child and many times since. On several occasions he approached the pageant about doing portraits of the performers, to no avail. Then at a certain point, Rolston enthused about the pageant sufficiently that journalist Christina Binkley pitched the Wall Street Journal on doing a feature on the pageant – and then suggested that Rolston be the photographer. The resulting 2015 article, “At California Pageant, Volunteers Inhabit Works of Art” provided Rolston the entrée with Pageant officials such that they allowed him to make portraits of the following year’s 2016 Pageant performers.

“Rolston used an extremely high-resolution camera (100 megapixels) and then printed the color photos on 60-inch sheets of cotton rag paper. As a result, the detail is incredible, the colors rich, the effect otherworldly.”

Rolston set up a studio backstage for photographing the costumed performers (the pageant uses two complete casts, so they can appear one week on, the other off) during breaks in rehearsals, at intermission and immediately after performances, and shot the dummy heads that are used as makeup guides.

Rolston used an extremely high-resolution camera (100 megapixels) and then printed the color photos on 60-inch sheets of cotton rag paper. As a result, the detail is incredible, the colors rich, the effect otherworldly. Although each shoot was fast, Rolston nonetheless had ideas of how he hoped to pose the performers. Rolston shot them “as is” in their costume and makeup and did no retouching. To the contrary, the imperfections we see (acne, crow’s feet, sagging skin) are, here, critical to finding the human in the faked. Rolston did engage in some digital manipulation (for example, in one image the hands are enlarged for reasons of proportion, as a sculptor might do). And if you look closely enough at the photos, you can see Rolston’s reflection in their iris— taking the shot

“Rolston’s Eve, taken from Rubens and Brueghel the Elder’s Garden of Eden, is no youthful nubile, but a mature woman whose face carries its share of sorrow and who grasps the apple at her side as if its secrets were her own.”

The results are striking: there is a golden girl, who seems very much a Greek nymph come to life. Her right palm faces forward in a sign we might see in a Hindu goddess. Although her eyes are open and piercingly blue, there is something of a somnolent haze about her, like a girl who has not yet awakened to her adulthood. In contrast, Rolston’s Eve, taken from Rubens and Brueghel the Elder’s Garden of Eden, is no youthful nubile, but a mature woman whose face carries its share of sorrow and who grasps the apple at her side as if its secrets were her own. The Laguna exhibition features a selection of images including portraits of the Pageant’s traditional closing tableau, Jesus and the Apostles from Da Vinci’s Last Supper. Rolston has said this project is an exploration of: “What is art?” and “Why do we make art?”

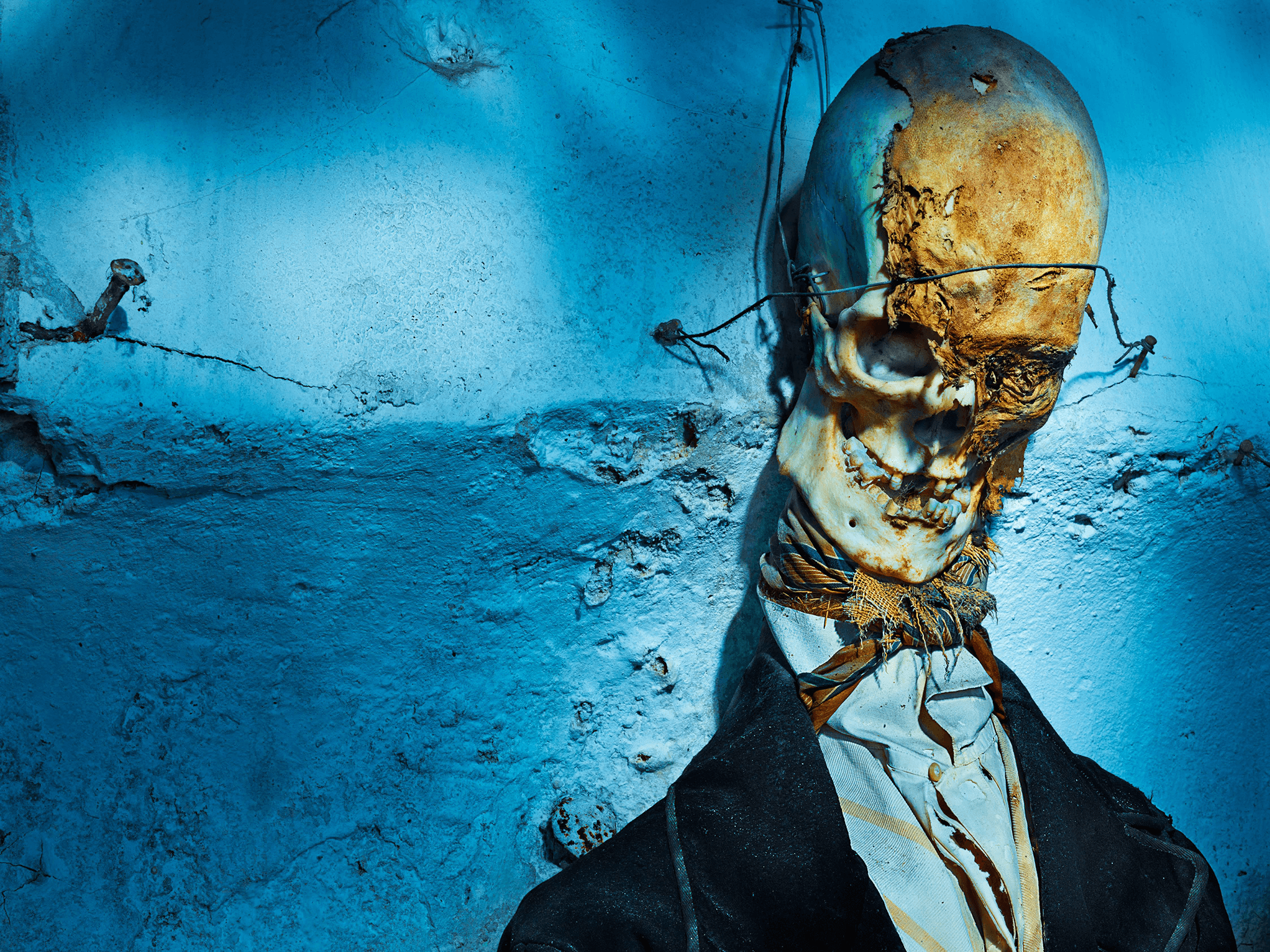

Rolston has also completed a third art project which he has not yet exhibited, “Vanitas: The Palermo Portraits” – which grapples with death. Rolston traveled to the Capuchin Catacombs of Palermo, Italy, where there is a collection of upright mummified corpses, fully dressed, ready for the Resurrection. But there is also a message posted at the crypt that states simply, “What you are now, we used to be. What we are now, you will become.”

I confess that at first, I struggled with Rolston’s stated premises. What can wooden dummies say about being human? What can non-artists creating a staged derivative of a real artwork teach us about making art? And what do mummified corpses in a crypt teach us about death?

“In Rolston’s portraits of the inanimate we see our own need to infuse objects with life - that is what makes us human.”

The answer came to me when watching a TED lecture on YouTube: according to historian Yuval Noah Harari, what distinguishes us from all other creatures, what makes us human, is our ability to be creative, to tell stories.

Therefore, in photographing ventriloquist dummies, Rolston is attempting to give life, as much as Geppetto to Pinocchio, or Dr. Frankenstein to his creature. In Rolston’s portraits of the inanimate we see our own need to infuse objects with life - that is what makes us human.

Similarly, when showing us the human in those who make a tableau vivant, the element Rolston adds to the already costumed and made-up is his art. Simple but true.

And in photographing the corpses in the Capuchin Crypt in Palermo, Rolston is giving us a vivid demonstration that what us separates us from corpses is our ability to make art of them. What is death if not the end of our potential to create?

One can argue then, that in Rolston’s editorial and commercial work, even in his work as a creative director, the collaborative constraints imposed by his subjects or employers are an application of his creative talent, but not art.

“The answer to the fundamental and existential questions Rolston asks in his art become simple: creating is what makes us human.”

By contrast, in photographing ventriloquist dummies, or stand-in performers in tableaux vivant, or even the staged corpses in Palermo, we can see that without Rolston’s intervention, without his creative act, they remain inanimate, imitations of art, rather than Art itself.

In this sense, the answer to the fundamental and existential questions Rolston asks in his art become simple: creating is what makes us human. Because we are human, we make art. And when we die, we cease to have the capacity to be creative. And, finally, as long as we are alive, we can appreciate Rolston’s “Art People: The Pageant Portraits” in all their beauty and mystery.

Program cover, second annual Festival of Arts and original presentation of “The Spirit of the Masters Pageant,” 1933. Festival of Arts, Laguna Beach.

Matthew Rolston: Master of the Pageant

By Louise Salter

It's safe to say that there is nothing quite like Pageant of the Masters anywhere in the world. It’s a theatrical experience which presents famous works of art on stage as tableaux vivants. In California, in the heart of Orange County’s Laguna Beach community, where townspeople have been collaborating on these tableaux for ninety years, nearly five hundred volunteers come together, year after year and summer after summer.

Pageant of the Masters tableau performance of Leonardo da Vinci’s fifteenth-century mural The Last Supper, 1936. Photograph mounted on board with cast members identified in pencil above. Festival of Arts, Laguna Beach.

The performers don hand- painted costumes and elaborate makeup to take their place on a framed proscenium and strike a pose. An orchestra plays an original score, and live narration unearths little-known facts about the works, to the delight of a spellbound audience. All this happens under the stars of the Californian great outdoors once daylight has faded and the magic hour is upon the world. On one such night in the 1960s, a young boy watched, delighting in the theatre, the illusion and the sheer glamour of transformation.

Andy Warhol, pictured at the Interview magazine office in his Union Square West Factory, photographed by Frances Inc, c. 1980s

That boy was Matthew Rolston. He grew up to become an image maker of exceptional talent. With a decades-long career, Rolston worked for Interview magazine (having been 'discovered' by its founder, Andy Warhol), The New York Times, Vogue, Harper's Bazaar, W, Rolling Stone; the list is long. Beginning in the 80s and over the next four decades, Rolston has focused his lens on Hollywood legends, giving them star power and creating timeless and iconic images. He is now in the enviable position of being able to choose the artistic projects about which he is most passionate.

Cyndi Lauper on the cover of Interview, photographed by Matthew Rolston, 1986

Rolston cast his formidable eye on the Pageant, and the results are glorious and singular. Removing individual performers in full makeup and costume from their painted settings, he gives new life to his Art People.

“This is not just documentation. It’s a creative process that took endless sittings and hours to get right: finding the precise moments a subject’s eyes come alive with humanity, revealing the person beneath the mask of makeup. ”

The portraits are best seen at full size, blown up so that the detail and gorgeous richness of colour can be fully appreciated. They may have been born from his past, but the portraits are very much Rolston's present, a continuation of his vivid and profound work.

Matthew Rolston, Barye, Roger and Angelica (Roger), 2016 (Courtesy Fahey/Klein, Los Angeles).

His creative endeavours bridge two worlds. One is a singular photographer's eye, and the other is a community's need for expression. Both share a love of flamboyance and theatre. But to unravel their connection, it's best to start with them individually.

Postcard view, Laguna Beach and Crystal Cove, c. 1930s

The early 20th century in California found two camps of photographers duelling it out, both groundbreaking, both wanting to be the force that moved the dial for photography on the world stage.

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984), Monolith, the Face of Half Dome, Yosemite National Park, California, 1927. Gelatin silver print, 11 x 8 1/8 in. (28 x 20.7 cm). Collection Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona

“Weston summed up [ƒ.64’s] approach to photography: “The camera should be used for a recording of life, for rendering the very substance and quintessence of the thing itself, whether it be polished steel or palpitating flesh.” ”

In 1932, in Northern California, eleven photographers formed the ƒ.64 group, including Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, and Imogen Cunningham. Weston summed up their approach to photography: “The camera should be used for a recording of life, for rendering the very substance and quintessence of the thing itself, whether it be polished steel or palpitating flesh.”

Edward Weston (American, 1886 – 1958), Nude, 1936. Gelatin silver print, 7 5/8 x 9 9/16 in. (19.3 x 24.3 cm). Collection Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona

At the same time in Southern California, in a nascent Hollywood’s dream factory, photographers George Hurrell, Paul Outerbridge, and William Mortensen rather saw the artifice of Hollywood as an art form itself.

Paul Outerbridge, Jr. (American, 1896-1958), No title (Hand with toilet tissue and red roses), 1938. Color carbro print, 16 1/8 x 13 in. (41 x 33 cm).

“Paul Outerbridge believed “Art is life seen through man’s inner craving for perfection and beauty - his escape from the sordid realities of life into a world of his imagining.””

Paul Outerbridge believed "Art is life seen through man's inner craving for perfection and beauty - his escape from the sordid realities of life into a world of his imagining. Art accounts for at least a third of our civilization, and it is one of the artist's principal duties to do more than merely record life or nature." Lights, sets, and Hollywood stars created the myths upon which our modern-day stories are built. Flawless skin in black and white prints looked like dreams come true, but in reality, actors’ faces were buried under heavy makeup, much like the performers in the Pageant.

William Mortensen (American, 1897-1965), L’Amour, circa 1936. Bromoil transfer, 11 3/4 x 10 3/8 in. (29.9 x 26.4 cm). Collection Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona

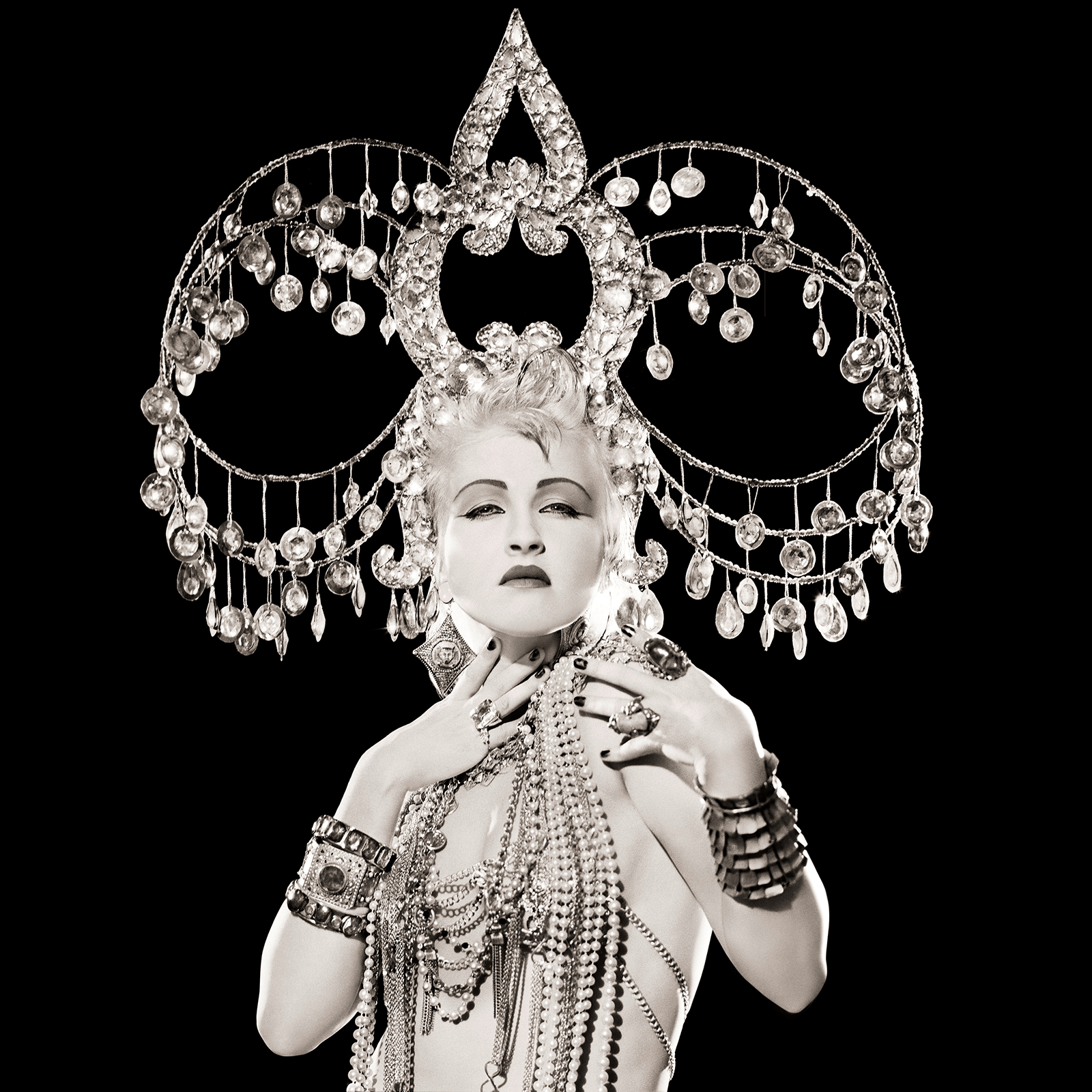

Rolston, clearly most informed by the second group, also creates dreams spun from cinematic gold. One of his most illuminating images is a portrait of Cyndi Lauper, circa 1986, from the series Hollywood Royale: Out of the School of Los Angeles.

“Rolston, clearly most informed by the second group, also creates dreams spun from cinematic gold.”

A goddess with alabaster skin, her magnetism shines out beneath an overwhelming headdress. She could have emerged from the Pageant stage, or a 1930s cinematic masterpiece, as photographed by Rolston. His power as an icon maker is on full display, and it's easy to see what attracted him to the Pageant.

Matthew Rolston, Cyndi Lauper, Headdress, Los Angeles, 1986, from the series "Hollywood Royale" (Courtesy Fahey/Klein, Los Angeles).

Pageant of the Masters began in Laguna Beach, California, in 1933, during America's Great Depression, in an imaginative attempt to lure visitors to the artists' colony to buy work. Its humble beginnings were not appreciated by local builder Roy Ropp, who called the "living pictures" an embarrassment. He decided to step in and help. A real stage was built with backdrops and seating, and his wife Marie took the helm of the artistic details. It worked. The foundations were laid, and the rest is history.

Stage built by Roy Ropp for Pageant of the Masters, Irvine Bowl, Laguna Beach, 1941. Festival of Arts, Laguna Beach.

Tableaux vivants were never a serious thing, points out longtime pageant scriptwriter Dan Duling, "The closest thing to being serious was educating children in the French court with a dress-up game. The next thing was putting it into a parlour game for the whole family. And then, the ultimate version gave producers on burlesque stages in the early 20th century an excuse to put naked women on stage. The police would be at the back of the theatre, and as long as they didn't move, it was an acceptable artistic expression. And they got away with that for many years."

Duling has written the pageant script for the past forty years, alongside the steadfast producer/director Diane Challis Davy. As he explained their work, "I would say we're using the tools of illusion with the emotional engagement of music and story to encourage people to perhaps just look at an artwork for a little longer." Together the two have guided and grown the Pageant to where it is today: a professional, vibrant, inclusive living theatre. The army of volunteers ranges in age from 5 to 80. We asked Duling why these people so generously donated their time. The answer is surprisingly simple: Community. They laugh together, build friendships, and care deeply about making the show successful. But it's also about being part of something bigger than the individual.

Something profound happens when so many people dedicate so much time creatively. The art being presented, although highly artificial, holds truth. This leads to the burning question at the heart of Rolston's work, and why he was drawn to the people of the Pageant: Why make art? It's a fascinating and very human question.

It took years of persuading all those involved with the Pageant for Rolston to secure permission to photograph it. He sent a letter and waited an entire year for a response, as the Pageants's board of directors did their due diligence. What most fascinated him were the details.

Pageant of the Masters tableau performance of Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s 1767 painting The Swing, 2015. Festival of Arts, Laguna Beach.

“[In the Pageant,] a stage gown is not what it seems, not fabric but painted on canvas with the shadows painted in, so when the costume is lit, all of the dimension disappears, but the beauty stays. Pure illusion. ”

Except for the wigs worn in the finale (a tableau of Leonardo DaVinci's The Last Supper,) there is no real hair in the Pageant, because all the headpieces are constructed: sculptures made from latex to appear as hair, or as a hat and, of course, entirely unrealistic makeup. But the artifice is complete once the light hits, along with the help of braces and stirrups to hold the pose. Perspective is everything.

Matthew Rolston. Da Vinci, The Last Supper (Saint Philip the Curious), 2016 (Courtesy Fahey/Klein, Los Angeles).

It's a piece of pure magic, old-fashioned and comforting, and starkly contrasts with our own age’s technological speed, exhausting even for the most fervent believer in the wonders of our brave new techno world. The Pageant is time given back. We can sit and linger on an image and marvel at these multiple human endeavours; the artist that painted the original work and the people creating the art on the stage.

In the Summer of 2021, the exhibition of Rolston’s Art People: The Pageant Portraits opened at The Laguna Art Museum. The show was curated by Dr. Malcolm Warner and brought together three pillars of the artistic community: the museum, the pageant, and the people. It signified a rebirth for the community emerging from the covid lockdown. Julie Perlin Lee, who took over from Dr Warner as the museum executive director during the lockdown, said, “The exhibition re-energised the museum. It was a tremendous moment in time. It’s hard to describe the energy in the room. This opening was extra special for so many reasons, mostly to be together but also to be again with art. For so many of us, it’s what feeds our souls.”

““The exhibition re-energised the museum. It was a tremendous moment in time. It’s hard to describe the energy in the room. This opening was extra special for so many reasons, mostly to be together but also to be again with art.” ”

Perlin Lee said, “The artists who started the museum also started the Pageant. We come from the same genesis, so in different ways, we have highlighted our shared history over time but never had an exhibition based solely on the pageant and at this scale. It took a third person’s point of view to focus on the pageant, which is what Matthew did. Obviously, when someone else is speaking for you, it’s very powerful.”

As Rolston says in Laguna Art Museum’s lavishly illustrated catalog of its exhibition, Art People: The Pageant Portraits, "More than a record of the Pageant of the Masters' costumes, makeup designs and intricate staging motifs, Art People is a series of portraits of human beings. It attempts to portray their personal dignity, their inner life and conflicts, all within a fascinating conceit that centres on the somewhat mysterious subject of the making and appreciation of art. Art is human. We are art."

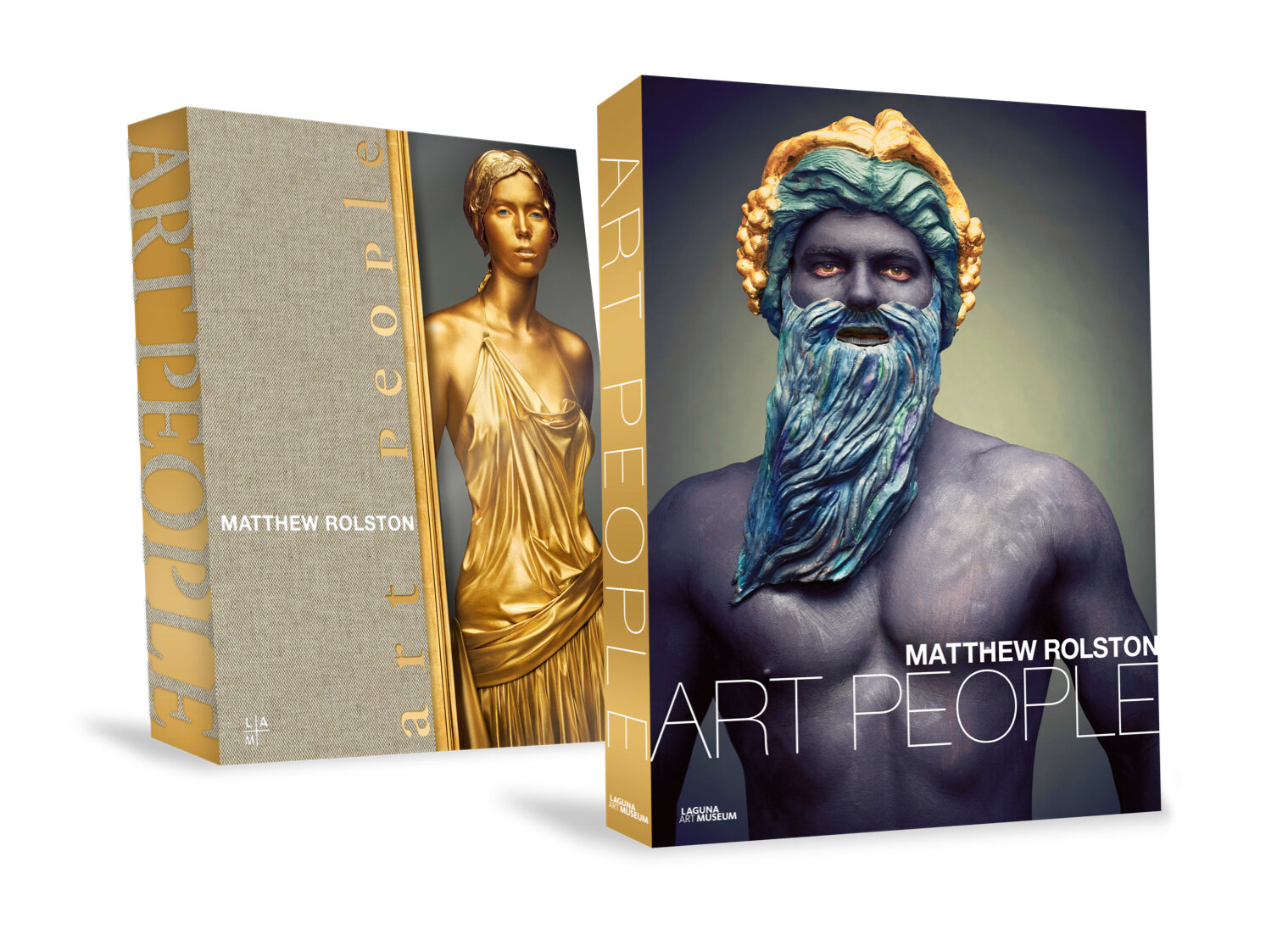

Matthew Rolston, Art People: The Pageant Portraits, Exhibition Catalogue, Collector’s Edition. Published by Laguna Art Museum.

Below and behind the stage are the makeup and dressing rooms. The top shelf of the makeup room is lined with a sea of floating painted Styrofoam heads, making palpable the Pageant’s analogue nature. Not even a polaroid in sight, every character has their makeup painted on a dummy head, a guide for their nightly re-creation. With roughly 45 works of art to assemble, it’s a lot of characters to prepare.

Makeup area backstage, Pageant of the Masters, 2014. Festival of Arts, Laguna Beach.

“Below and behind the stage are the makeup and dressing rooms. The top shelf of the makeup room is lined with a sea of floating painted Styrofoam heads, making palpable the Pageant’s analogue nature.”

Up close, the makeup looks like smudges and impressions of shading. The costumes, made from canvas and painted in bold painterly strokes, only make sense when viewed from a distance. A 3-foot smudge becomes the shading on a Venetian gown in a Tiepolo painting. It’s all about perspective and illusion. Within the wooden frame, the scenic artists and master carpenters have meticulously created representations of the paintings and other works using light to flatten the image. It’s a bravura sleight of hand.

A practice make-up head, Pageant of the Masters, photographed by Matthew Rolston for the Wall Street Journal, 2015

“The images reveal the process. It begins with the makeup design on the dummy head... ”

Pageant of the Masters tableau performance of David Hockney’s 1968 painting American Collectors (Fred and Marcia Weisman), 2016. Festival of Arts, Laguna Beach.

The images reveal the process. It begins with the makeup design on the dummy head; then we see the performer as Marcia Weisman, in costume and fully made up. The final reveal of Hockney’s painting American Collectors (Fred and Marcia Weisman) is re-created in tableau on the Pageant stage.

Matthew Rolston, Hockney, American Collectors (Marcia Weisman), 2016 (Courtesy Fahey/Klein, Los Angeles).

“I feel that art-making is one of the things that makes us most human,” Rolston says. “It starts with our awareness of self. We know we’re alive and we know we’re going to die. We can’t change that. And we have this idea of perfection, but we can’t achieve it. Art is a way of explaining ourselves to ourselves. Art is imagined. Money is imagined. Movie stars are imagined. Even goddesses are imagined.”

Matthew Rolston’s Art People

By Patricia Lanza

A “polymath” is the rare individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, one who is able to draw on complex bodies of information in order to solve specific problems. In the case of fine art and portrait photographer Matthew Rolston, think of an artist whose practice spans the gamut – magazine covers, advertising, creative direction, music videos, publishing, education, and now, personal fine art projects.

After he was “discovered” by none other than Andy Warhol for Warhol’s Interview magazine, Rolston went on to work extensively for other prominent publications, such as Vogue, Vanity Fair, Harper’s Bazaar, and over a hundred covers for Rolling Stone.

Rolston has many disparate projects in seemingly unrelated fields – from the gallery wall to creative direction for some of the world’s leading hoteliers – all of which are united by a powerful sense of what he calls “romantic notions about humanity.” Just take a look at his website (matthewrolston.com) and you’ll get the idea.

Rolston’s latest endeavor is an expansive exhibition at Laguna Art Museum in Laguna Beach, California. It’s called Art People: The Pageant Portraits and was curated by Dr. Malcom Warner, the museum’s former executive director. Eighteen large-scale works, some made of multiple panels, fill the galleries of his solo exhibition, accompanied by a lavishly illustrated catalog. The most awe-inspiring of Rolston’s works is comprised of twenty-six individual photographs and commands over thirty feet of wall space. It’s entitled The Last Supper. Coincidentally (or perhaps not), the final work of Rolston’s mentor, Warhol, was also entitled The Last Supper.

“The most awe-inspiring of Rolston’s works is comprised of twenty-six individual photographs and commands over thirty feet of wall space.”

The exhibition showcases Rolston’s larger-than-life portraits of the volunteer actors who pose on artfully crafted sets in shimmering costumes and makeup to embody “art people,” that is, the figures in well-known works of art brought to life in an annual tableau vivant entertainment called Pageant of the Masters. This elaborate and perhaps eccentric production is a beloved Southern California tradition that has taken place every summer in the art colony of Laguna Beach for over eighty years.

Rolston attended Pageant of the Masters many times with his family as a child and remembers being overwhelmed by “the theatricality of it all.” He has said that being exposed to the Pageant as a youngster was a pivotal moment leading to his career as an artist.

Searching for a photographic subject to express ideas about artmaking and its place in the human experience, Rolston returned to the Pageant in 2015 on assignment for the Wall Street Journal. Far from creating the works currently on display, Rolston was tasked with documenting the Pageant process backstage which gave him the unique opportunity to meet the Pageant’s creators. That first meeting led him to eventually receive rare access to the pageant performers in order to create the body of work he now calls Art People.

In Rolston’s brilliant, richly hued portraits, he offers not only a deeply poignant and personal account of Pageant of the Masters and its participants, but also underscores the uncanny ways in which these works bring out fundamental aspirations of the human spirit and its underlying impulse towards art creation.

“Laguna Beach’s Pageant of the Masters is in itself an incredible meta-journey into art making. It’s a form of art about art about art. So is Art People.”

Said curator Warner, “By isolating his subjects, and presenting them in such high definition that the painted-on brushwork and patinas reveal themselves as the makeup that they are, Rolston brings out the strange, melancholy poetry of real people impersonating painted and sculpted ones.”

Laguna Beach’s Pageant of the Masters is in itself an incredible meta-journey into art making. It’s a form of art about art about art. So is Art People. “It’s a kind of hall of mirrors,” notes Rolston. “Art People is also a document of people. These are, after all, portraits of the volunteers who perform in the Pageant. They themselves are Art People.”

Q & A

Can you explain the nature of your exhibition?

Matthew Rolston: This is my first solo institutional show on the West Coast. My work has been shown all around the world in galleries and museums. I’ve taken part in both solo and group shows but I’ve never had a solo institutional show in my home state of California.

The exhibition itself includes eighteen high-resolution photographic works, portraits of the volunteer actors in a local art tableau vivant entertainment called Pageant of the Masters. The images are printed on a monumental scale.

The aim is to create a visual conversation between painting and photography. Not by using any photographic trickery, no false brush strokes added in post. Instead, I’ve chosen to photograph subjects who themselves are painted (as are their costumes). The high-resolution, grand-scale format, printed in archival pigments on rag paper, furthers this painterly quality. There are portraits, diptychs, and elaborate groupings, sometimes juxtaposed against images of the makeup templates created by the Pageant staff – that is, makeup painted onto Styrofoam heads. These are fascinating objects in and of themselves.

The museum has also produced a somewhat unusual exhibition catalog. It’s a collaboration between myself and the exhibition curator, Dr. Malcom Warner, the museum’s recently retired executive director. I say “unusual” because the catalog is designed in a concertina format, folded rather than bound, and it’s offered in two versions, a beautifully produced standard edition as well as a deluxe limited and numbered collector’s edition, featuring a signed print enclosed in a folio.

What is Pageant of the Masters? Why did you choose to base your series on that event?

Matthew Rolston: Pageant of the Masters is known for its live presentations of art masterpieces. It has taken place every summer night for over eighty years in a beautiful outdoor amphitheater in Laguna Canyon, not far from the town’s main beach. The Pageant is an elaborate tableau vivant entertainment in which volunteer actors are painted and costumed, placed on artfully crafted and lighted sets, and reenact pivotal historical figures and works from art history, from antiquity through twentieth century modernism.

I was searching for a way to use portraiture as both a commentary and examination of a very simple human question: why do we make art? There is no one answer to this question. My hope is that the viewers will engage with my images and ask themselves that question, thereby beginning an interior dialogue into this somewhat mysterious subject.

What was your process? How did you go about it?

Matthew Rolston: I attended the Pageant many times as a child with my family. It was a formative experience of my youth and in some ways led to my identifying as an artist. I’ve always been fascinated with the Pageant – the stagecraft, the illusion, and of course its subject, art.

I returned to the Pageant as an adult at exactly the moment when I was searching for a “way in” to a visual discourse about artmaking. Upon that visit I immediately knew I had found the perfect subject. It took a while to gain the trust of the Festival of Arts of Laguna Beach, which is the producer of Pageant of the Masters, but ultimately, through the courtesy of the Festival’s board and the project being championed by the Pageant’s longtime director, Diane Challis Davy, I was able to gain rarely granted access to the performers and spent several weeks photographing them in a makeshift studio set up backstage during the run of the show.

You’re known for celebrity portraiture and glamour, is there a connection here?

Matthew Rolston: People know my celebrity portraiture as a celebration of glamour, and it often references the ‘old Hollywood’ values of impossible perfection. As I’ve grown older, I’ve begun to realize that the pursuit of impossible perfection is a denial of aging and death. I also began to realize that the gorgeous and the grotesque are deeply intertwined. They are really two sides of the same coin. This has become a fascination. There is tremendous poetry to be found in imperfection. I sense a kind of bravery in human beings as they attempt to deny their own humanity and take on the guise of ‘gods’ in a futile search for perfection.

With this series I’ve tried to show the humanity behind the theatrics of subjects masked in layers of caked-on makeup, body paint, and metallic powder. Far from glamourous Hollywood stars, my portrait subjects for Art People stem from all walks of life and social backgrounds. I sensed something both tragic and noble in the act of ordinary people choosing to impersonate famous artworks.

Ultimately, both the glamorous and the ordinary, the gorgeous and the grotesque, are united as expressions of the glory and scourge of humanity…our fertile imagination.

What are art people? Why did you choose this title?

Matthew Rolston: “Art people” is a moniker often applied to members of the contemporary art world, a loosely organized international community – a glamorous and global crowd— of art fair-attending collectors, artists, curators and of course, the all-important gallerists.

Art People: The Pageant Portraits is something very different. These Art People are not those art people, so perhaps there’s an element of irony in my choice of title. This project is a record, through photographic portraiture, of the volunteers who allowed themselves to be painted and costumed as living works of art in the Pageant’s 2016 production, all in service of a simple existential question: why do humans make art?

Matthew Rolston at Laguna Art Museum

By Liz Goldner

If art is a metaphor for life, this photographic display is an exploration of humanity’s creative energy along with its search for meaning and identity. Or as Nigel Spivey, a classical scholar, explains in this exhibition’s catalog, “’Art People’ advances a statement about our identity as human beings: how we define ourselves as creatures who are creative, and as individuals whose individuality is part of that creative power.”

“If art is a metaphor for life, this photographic display is an exploration of humanity’s creative energy along with its search for meaning and identity.”

Inspired by this truism, “Matthew Rolston, Art People: The Pageant Portraits” takes a multi-faceted approach to photography—with its portraits of people, made-up and dressed to look like figures in paintings and sculptures; they are actually characters who appear in Laguna Beach’s theatrical event, Pageant of the Masters, which features the centuries-old art form known as “tableaux vivants”.

The outdoor Pageant, dating back to 1932, presented for eight weeks every summer, showcases volunteer cast members wearing detailed makeup and costumes, posing in elaborate painted sets and theatrical lighting. The resulting tableaux vivants or “living pictures” depict artworks over the centuries, from those by old masters to contemporary artists.

While the living pictures are appropriated from actual art pieces, some of that art may have been originally based on photography, as with the David Hockney painting, “American Collectors,” or based on created scenes, populated by real people who posed as historical figures. An example of a painting reportedly constructed from a posed scene is Leonardo da Vinci’s “The Last Supper.” This historic painting has been the Pageant’s final living picture for many decades.

“The resulting photographic portraits explore the humanity within us all, along with the deeper vicissitudes of artworks, including the “hall of mirrors” aspects of artmaking.”

“Art People” was created by Rolston, a visionary artist, photographer and director, who has admired Pageant of the Masters since his childhood. Drawing on his decades of fascination for the event, he set out six years ago to shoot individual portraits of pageant cast members while they were not posing onstage for the actual living pictures. Malcolm Warner, former Executive Director of Laguna Art Museum, explains this process in the catalog: “By isolating his subjects, and presenting them in such high definition that the painted-on brushwork and patinas reveal themselves as the makeup that they are, Rolston brings out the strange, melancholy poetry of real people impersonating painted and sculpted ones.”

The resulting photographic portraits explore the humanity within us all, along with the deeper vicissitudes of artworks, including the “hall of mirrors” aspects of artmaking. Some of Rolston’s photos are then based on figures from Pageant living pictures, which are themselves based on paintings and sculptures, which are in turn derived from photos or staged scenes.

His “Da Vinci, The Last Supper (Saint Philip The Curious),” depicting the character St. Philip from Da Vinci’s “The Last Supper,” is a portrait of a Pageant cast member, heavily made-up, coiffed and dressed to mimic a person from the time of Christ. Portraying a man wearing a somber expression, it eclipses the present, bringing the viewer to a solemn scene from millennia ago.

Rolston’s “Barye, Roger and Angelica,” gracing the cover of the catalog, and serving as a hallmark of the show, is of a young woman painted entirely in gold, including her draped gown and hair, with only her piercing blue eyes revealing her living identity. She is a human being, segueing to become a sculptural work—thereby inverting the Pygmalion myth.

“This astonishing exhibition, elevating portrait photography to a profound and humanistic level, explores the nexus where people transcend their limitations to create great art.”

Most other portraits in this exhibition are of figures from classic historic paintings and sculptures. Yet Rolston’s “Hockney, American Collectors (Marcia Weisman)” is a contemporary portrait of a Pageant cast member posing as the deceased art collector, Marcia Weisman. The original 1968 Hockney painting, “American Collectors,” in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, was created from a photo of Weisman and her husband Frederick Weisman posing beside their home. The Pageant model in this photo brings Weisman to a more humanistic level than is displayed in Hockney’s original painting.

Rolston wrote for the “Art People” catalog, “Art is human. We are art.” Indeed, this astonishing exhibition, elevating portrait photography to a profound and humanistic level, explores the nexus where people transcend their limitations to create great art.

Famous Photographer Focuses on Living Pictures

By Jacqui Palumbo

Each summer night, on an open-air stage in Laguna Beach, California, volunteer performers assemble themselves into "tableaux vivants" - living pictures. They work quickly under the cover of dimmed red or blue lighting, which obscures their movement. When the bright stage lights go on, they have formed near-identical replicas of famous artworks - Edward Hopper's shadowy mid-century painting "Nighthawks," perhaps, or Diego Velasquez’s mysterious, regal family portrait, "Las Meninas."

For most in the crowd at the annual Pageant of the Masters, the illusion holds perfectly for each 90-second scene. Look closely, however, and you may see the figures move ever so slightly, or the creased lines of makeup on skin.

Photographer Matthew Rolston, whose new exhibition, called “Art People”, at the Laguna Art Museum features striking portraits of the volunteers who transform themselves into famous artworks, did just that. "I took my field glasses - binoculars - and I looked at those faces on the stage up close, with their crumbling makeup and such," he said in a video interview.

The photographer may have made a name for himself shooting glamorous celebrity portraits for Andy Warhol's Interview magazine in the 1980s, but at the pageant, Rolston "looked at the imperfection of it all," he said, adding: "And that is what really moved me."

Shot backstage against plain backgrounds, the photographs take performers out of their familiar settings -- the intricately designed stages modeled on the artworks they imitate.

““In my images you can hopefully sense a slightly haunting quality of identity coming through the layers of artifice.””

The volunteer who plays Eve in a 17th-century painting by Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel the Elder, for instance, is transported from the Garden of Eden to a plain dark backdrop, her red hair tumbling down her shoulders as she clutches the infamous apple. The impersonators of a 1968 David Hockney painting, meanwhile, have been plucked from the artist's color-blocked suburban scene, making their painted garments and exaggerated makeup appear all the more uncanny.

"When they're on stage, they're not individuals so much as figures in a tableau," Rolston said. "And in a way, their personal identity is removed for that experience for the audience. In my images you can hopefully sense a slightly haunting quality of identity coming through the layers of artifice."

A Long Community Tradition

Pageant of the Masters, part of the Laguna Beach Festival of Arts, has been held in the coastal city for nearly a century. The first of its "Living Pictures" shows, in 1933, featured a reimagination of James McNeill Whistler's famous portrait "Whistler's Mother," among other artworks.

In the 19th century, Impressionist artists flocked to coastal California, and Laguna Beach became a thriving creative community. But when the Great Depression hit, the city needed to encourage spending and position itself as a tourist destination, according to the pageant's longtime director, Diane Challis Davy. "It started from very humble beginnings," she said.

"They put it on in the open air," she added of the early shows. "They didn't have stage lighting; they cut up curtains and tablecloths to make the costumes. It was rather makeshift."

Today, Pageant of the Masters is a huge production. Over the course of 90 minutes, performers re-create 40 artworks - including paintings, sculptures and mixed-media works - around a different theme. There's a narrator, who gives the crowd a brief art history lesson with each work, and a live orchestra that produces original compositions. Challis Davy estimates that 140,000 people see the pageant at the Festival of Arts’ Irvine Bowl Recreation Park in a typical year.

““They didn’t have stage lighting; they cut up curtains and tablecloths to make the costumes. It was rather makeshift.””

Having only ever been canceled for World War II and the Covid-19 pandemic, the pageant is returning to form with the theme "Made in America." It features re-creations of photographs by Dorothea Lange and paintings by Hopper and Norman Rockwell, among others.

But no matter the theme, the show has - since 1936 - always closed with Leonardo da Vinci's iconic mural "The Last Supper." It's a fan favorite that helped bring wider attention to the show, Challis Davy said.

"The pageant got nationwide publicity, because everyone thought it was so charming that the community would reenact 'The Last Supper,'" she said.

The Art of Illusion

For Rolston, who had not attended the pageant since childhood, returning as an adult in 2016 to create the “Art People” series still conjured the same magic.

"There is a sense of wonder at the illusion because what they do is so amazingly well crafted," he said. "You really think for a few moments that you're looking at an artwork, and then you realize it's human beings that are painting and costumed. It's a simulacra and an illusion - somewhere between humanity and a depiction of humanity. And that has some intrinsic, almost primitive fascination for people."

The illusion is maintained with carefully applied makeup, body paint and costumes that emulate light and shadow, according to Challis Davy. The scenes are "flattened" using stage lighting that eliminates shadows, and the artworks are all re-created within a large frame.

““It’s a simulacra and an illusion - somewhere between humanity and a depiction of humanity. And that has some intrinsic, almost primitive fascination for people.””

As well as painting people and props, the set artists use projectors to cast a scene onto the stage, filling in the image "like a paint by numbers," Challis Davy explained. Having long used old Kodak slide projectors, producers now also use digital video to craft "projections of images and photographs - so it really helps with the storytelling," she added. Over the decades, technological advancements like LED lighting and improved textile paints have also aided production.

The show has dabbled in live action, too. Challis-Davy's favorite scene, from a few years ago, saw performers create a replica of an Edo-period Japanese woodblock print featuring floating cherry blossoms and imitation snowfall.

Rolston even had the opportunity to personally participate in 2016, the year he photographed his “Art People” portraits. He was offered the role of Judas in "The Last Supper," though he requested Saint Matthew instead. (He had to stand on a box to meet the height requirement, the photographer recalled with a laugh.)

"The weirdest part of that experience was when the curtain went up," he said. "There's a collective 'ooh ahh' from the audience, and then applause. And I'm standing there doing absolutely nothing, because that's the job: holding perfectly still for 90 seconds. It was so strange; they're applauding nothing. But of course, they're applauding the stage illusion."

Arts Intel Report

MATTHEW ROLSTON, ART PEOPLE: THE PAGEANT PORTRAITS

By J.V.

A Laguna Beach tradition, the Festival of Arts’s Pageant of the Masters has been enlisting local volunteers to re-create famous works of art, from Hockneys to Leonardos, since 1933.

“Stripped from their context, Rolston’s monumentally-scaled portraits are at once haunting and moving.”

The American photographer and artist Matthew Rolston, a Warhol discovery who rose to fame in the 1980s alongside Herb Ritts, Bruce Weber, Annie Leibovitz, and Steven Meisel, attended his first Pageant when he was eight, and has remained fascinated by its tableaux vivants. In this exhibition, Rolston zooms in on the Pageant volunteers who create those “living pictures.” Stripped from their context, Rolston’s monumentally-scaled portraits are at once haunting and moving.

Famed Photographer Matthew Rolston Explores a Southern California Tradition

IN AN EXHIBITION AT LAGUNA ART MUSEUM, THE L.A. NATIVE CELEBRATES ”ART PEOPLE”—AND THE BEAUTY OF IMPERFECTION

By Merle Ginsberg

Back in the ’80s and ’90s, a triumvirate of L.A. celebrity photographers suddenly snagged most of the covers of American glossies. This then emerging, now renowned, trio shot major celebs, album covers, as well as extensive entertainment industry and fashion photography: Greg Gorman, Herb Ritts, and Matthew Rolston. But after years of shooting Madonna, Janet Jackson, and the rest of the usual suspects a number of times, L.A. native Rolston decided to diversify his portfolio, so to speak.

With a restless mind and endless thirst for culture, Rolston jumped to directing, shooting music videos for the likes of Mary J. Blige and Christina Aguilera, doing video promos for Sex and the City, and working on a plethora of commercials (the Gap’s famous “Khakis Swing,” Revlon, Visa, Guess, to name a few). Reinvention became a natural part of his process. Rolston’s next move was to morph into a creative director who took on a number of significant independent hotel projects, including L.A.’s the Redbury for developer Sam Nazarian, the Virgin Hotel group for Sir Richard Branson, the Milford in New York (New York’s largest hotel), and many more. But Rolston’s ultimate goal became a fine art practice. “I’m motivated by questions I have about human behavior,” he says, “The answers reveal themselves when I ask them in the work.”

“Rolston’s ultimate goal became a fine art practice. “I’m motivated by questions I have about human behavior.””

To wit, Rolston now spends time teaching a master class that he authored at his alma mater, ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, and making art that’s completely self-initiated. And he’s come full circle: some of Rolston’s current collectors are the very celebs he used to shoot. He’s created four books of art photography and subsequent gallery shows: one a compendium of his Hollywood portraits from the 1980’s, ‘Hollywood Royale’, and three other books of unique pictures: close-up portraits of a rare collection of dummies at the obscure Vent Haven ventriloquist museum in Fort Mitchell, Kentucky (a project called ‘Talking Heads’); grand scale portraits of ancient, ashen Christian mummies from the catacombs of Palermo, Sicily (this one called ‘Vanitas’), and now, monumental portraits of makeup-slathered cast members at Laguna Beach’s Pageant of the Masters which he calls ‘Art People’. Some of the prints are over eight feet tall.

Every summer, crowds convene under the stars each evening in an outdoor amphitheater to watch everyday Laguna citizens embody works of art in the famed “tableaux vivant” show. Rolston’s enormous portraits of the performers are currently on view in the exhibition Matthew Rolston, Art People: The Pageant Portraits at Laguna Art Museum.

Los Angeles asked Rolston how he came to be obsessed with what he calls “Art People”—and how actually he came to be one of them.

How did you come to photograph the players of Pageant of the Masters? The Laguna Festival of the Arts has never allowed a photographer to shoot it, despite many requests.

Seven years ago, I went down to the pageant with friends; we’d all confessed to being ‘Pageant Heads’—just obsessed with the yearly pageant. I took my Nikon field glasses; we had very good seats and we could see all the painted faces up close. I could feel how excited these people, both onstage and in the audience, were about art and embodying art themselves. But under closer scrutiny, with those field glasses, I could see their makeup and costumes—they’re not perfect. The illusion of the show at 50 feet away is uncanny. You absolutely believe what’s presented live on stage is a painting. But it’s the imperfection up close that’s so beautiful to me. I never gave up asking if I could shoot it—and finally, the board of directors of the Festival of Arts, which produces the pageant, agreed.

That’s funny about imperfection, because you’re known as the man who created “beauty light” for your celebrity portraiture of stars like Madonna, Cyndi Lauper, Annette Bening, and Michael Jackson in magazines like Rolling Stone, W, Harper’s Bazaar, Oprah, Vanity Fair.

Sure. But my fine art is not commercial photography—I’m not selling any thing or any one and I’m not working for anyone other than myself. It’s a subject I choose; it’s not assigned. For me, this process is more about stripping artifice away than perfecting it—creating it. I was stuck on a particular issue: how do I go about investigating the act of art making? This series of portraits attempts to propose a question: is art-making a defining characteristic of being human – and why do we make art anyway? This is what I was looking to explore. After we went to the pageant that night seven years ago, I knew I’d found the perfect subject and the perfect title: ‘Art People’.

Can you describe what you mean by ‘Art People’?

The collectors, the critics, everyone who goes to Art Basel in Miami, Frieze, museums, galleries, auction houses—those are art people. And the people in Pageant of the Masters – people who take off every night of the summer to become living art, they’re art people too. Just of a very different kind. So perhaps there’s a sly joke in my naming choice.

You seem to be drawn to all things SoCal since you grew up here. How did Los Angeles shape your imagination, your work?

It’s true. Mine is such a Los Angeles story. I did grow up in Hollywood after all, and don’t they call Hollywood the dream factory? And as a photographer, I spent many years of my practice in that world. So there’s that. And growing up here, some of the traditional things families do with kids is take them to places like Disneyland, the Pageant down in Laguna, and museums like the Huntington Library in San Marino. Those early experiences had a powerful impact. I was around eight years old when I first visited the Huntington with my family. I saw Henry Huntington’s original core collection of 18th century English portraiture. The Gainsboroughs, the Lawrences, the Romneys. From that point on, I became fascinated with grand scale portraiture and the Greek revival period. Classical shapes. Hellenism. There’s a larger-than-life-size bronze there called ‘Diana the Huntress’ by Houdon. I still go to visit that piece on a regular basis, it’s a touchstone and I think you can see all those early influences in this work. The other big influence was my mom’s collection of magazines, her Vogues and Bazaars, which I devoured as a kid. She had kept all the great issues from the 50’s and 60’s. The magazines were much more artistic then, with the work by Avedon and the editing of Diana Vreeland. All early Matthew DNA.

Is that how you wound up shooting for so many magazines?

I guess so. I always loved the magazines. I started off with Andy Warhol and Interview magazine in New York—I was probably 20. It’s funny, but Andy’s work and aesthetic wound up having a very long-term effect on me. I watched him in the studio, I read all his books, I trailed after him at many a social event in the late 1980’s. And remember that Andy’s main art was always portraiture, and that’s what I do. No doubt there’s a fair amount of Warhol influence in everything I’ve attempted.

Do you think the things we’re exposed to when we’re young can get permanently imprinted on our imaginations?

Well, I have gone to the Huntington and the Pageant countless times, so in my case definitely yes. My intention with “Art People” may be a little sarcastic, but it’s also personally meaningful. People visit the pageant to see art people. People perform in the pageant to be art people. The theme of the exhibition and the museum’s catalogue is art about art about art —a kind of conceptual hall of mirrors. I idealize my subjects always, but this work is not about the pursuit of perfection. Quite the opposite. Every mole, wrinkle, acne on a forehead is right there, through the makeup and paint. Perhaps it’s a reaction against the surface perfection of my Hollywood work. This whole project is a celebration of the imperfect. I don’t think I would have come to this appreciation at an earlier part of my career.

Matthew Rolston’s Solo Photography Exhibition Opens at Laguna Art Museum

By Annie Block

Photographer Matthew Rolston’s client roster is impressive. Mary J. Blige, L’Oréal, Vogue, Virgin Hotels—the list goes on. For the past decade, however, he has trained his lens on creating fine art. One series in particular is from 2016, although it originated from when Rolston was a child.

“For the past decade, Rolston has trained his lens on creating fine art.”

Raised in postwar Los Angeles, Rolston was exposed to both classical art and Hollywood imagery, around the city and at area cultural institutions and festivals, including Pageant of the Masters in Laguna Beach. The 88-year-old annual event brings famous paintings to life—think Leonardo da Vinci’s “The Last Supper” and Edward Hopper’s “Nighthawks”—in a live musical production otherwise known as tableau vivant, or living pictures.

“Rolston says the project is ‘art about art about art.’”

Five years ago, Rolston was granted unprecedented backstage access to the pageant, setting up a makeshift studio to shoot the fully costumed performers during dress rehearsals and intermissions. The result is “Matthew Rolston, Art People: The Pageant Portraits,” an 18-image exhibition at Laguna Art Museum that captures tableaux from that year’s theme, “Partners,” drawn from such artworks as Antoine-Louis Barye’s “Roger and Angelica” and Harriet Whitney Frishmuth’s “The Dancers”, all of which Rolston rendered in monumental format (Angelica is 8 feet tall). He says the project is “art about art about art.”

Matthew Rolston, Photographer to the Stars, Turns His Eye to Pageant of the Masters

By Jane Greenstein

“Matthew Rolston, Art People: The Pageant Portraits” is the photographer’s latest attempt to pull back the layers of humanity through portraiture. This time Rolston is making art about people who re-create fine art, taking on as his subject the volunteers who are costumed as part of the annual Pageant of the Masters in Laguna Beach.

“‘Art People’ as a project is intrinsically connected to the community of Laguna Beach,” he wrote in an email. “The Pageant has been a beloved tradition in Laguna for over eighty years, and very much by and for the community. Let’s remember that the town began as an artist’s colony and that the inception of the Festival and Pageant and the museum itself are historically connected.

“Because of the pandemic the arts community of Laguna (like everywhere) has been nearly shut down for a year, so this event can be seen to mark a kind of rebirth or renaissance for arts in the town of Laguna. I am really proud that my piece knits together the threads of Laguna’s art, history and community and is therefore newly resonant at this particular time.”

““I am really proud that my piece knits together the threads of Laguna’s art, history and community and is therefore newly resonant at this particular time.””

From Popular to Fine Art

Rolston’s foray into fine art is the latest chapter in a storied career. He’s photographed everyone from Michael Jackson and Prince to Madonna and Beyoncé for publications including Interview, Rolling Stone, Vogue and Vanity Fair, and he co-directed Christina Aguilera’s award-winning “Candyman” video with the star herself. Rolston has also photographed iconic advertising campaigns for brands such as L’Oréal, Revlon, and Estée Lauder and as a creative director has assisted in the branding of boutique hotels operated by SBE Entertainment and Richard Branson’s Virgin Hotels, among others.

Over the last decade Rolston’s focus has shifted from promoting beauty to dissecting it. “Art People” follows “Talking Heads: The Vent Haven Portraits,” which depicted ventriloquist dummies housed in the Vent Haven Museum in Fort Mitchell, Kentucky.

“I was searching for a way to express an idea about projection,” he said. “That’s where I started. Everything I do involves a projection of our own humanity into depictions of humans - simulacra. As a celebrity portrait photographer … you’re dealing with the iconography of celebrity. What are the ancient underpinnings of that - is that about idolatry - are there religious underpinnings to that?”

““One of those things that make humans unique, clearly, is art making - no other species that we know of does that .””

Both exhibits provoke the viewer to look closely: The Vent Haven figures take on human traits, while the pageant actors of “Art People” appear as almost mythic beings. “One of those things that make humans unique, clearly, is art making — no other species that we know of does that,” Rolston said in an interview. “What are the underpinnings of that, where does that come from?”

Art About Art About Art

“Art People” features 18 large high-resolution works printed on cotton rag paper (commonly used for watercolors). The works are presented in various formats and groupings, including individual prints and diptychs comprising a total of 48 individual photographs. One piece alone incorporates 26 individual prints stretching over 30 feet, featuring actors who take part in the traditional pageant finale, the re-creation of Leonardo da Vinci’s “The Last Supper.”

Because the subjects are photographed out of context of the paintings they’re representing on stage, they appear both God-like and grotesque. The meticulous fashioning of the subjects captures the styles of artists as diverse as Diego Rivera, Peter Paul Rubens, David Hockney, and da Vinci, and allows the viewer to imbue the characters with a new story. The elaborate body paint lavished on the actors accentuate different features, with some resembling statues or paintings.

Dr. Malcolm Warner, former executive director of Laguna Art Museum, who curated the exhibit, described the aesthetic Rolston was striving for in the exhibition’s catalog:

“In ‘Art People’, Rolston shows the performer, not the performance: the figure is removed from its context. By isolating his subjects and presenting them in such high definition that the painted-on brushwork and patinas reveal themselves as the makeup that they are, Rolston brings out the strange, melancholy poetry of real people impersonating painted and sculpted ones.”

““Rolston brings out the strange, melancholy poetry of real people impersonating painted and sculpted ones.””

The photos’ painterly quality and scale are exactly what Rolston was aiming for. “All are an attempt by me to elevate photography to the status of painting,” he said. “Not through trickery — not using some kind filter to look like brushstrokes — but by photographing subjects that themselves have a texture that looks painterly.”

The tableau vivant style of the exhibition has taken on another dimension, foreshadowing the pandemic year’s social media trend of people dressing up during quarantine as famous artworks. Rolston, who shot the “Art People” photos in 2016, couldn’t have predicted that his work would anticipate such a moment.

“The pageant is in some ways the modern mothership of all that aesthetic,” mused Rolston. “This was a project about representations of representations of representations: This is art about art about art. It couldn’t get more meta if it tried.”

Pageant Person

Rolston became entranced with Pageant of the Masters as a child when he and his family made regular pilgrimages from their Los Angeles home to the Laguna Beach Festival of Arts. Rolston, who was discovered by Andy Warhol while attending ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, considers the pageant a seminal influence. He considers it as inspirational as his mother’s Harper’s Bazaar magazines and family trips to Disneyland.

“It took my little childhood heart by storm,” he said. “The theatricality of it, the makeup, the stage lighting, the stage magic, the illusion.”

A chance conversation with friends a few years ago brought Rolston back to the pageant. His return meshed perfectly with his foray into fine art, specifically exploring the duality of beauty.

Rolston’s renewed interest in capturing the magic of the pageant led him through an odyssey of sorts: It involved gaining the trust of the festival organizers, befriending the volunteers, and even playing St. Matthew in the pageant’s re-creation of “The Last Supper.” Appearing onstage offered him an additional perspective, to be the one being looked at rather than orchestrating the action behind the scenes.

This new direction was further inspired by the progression of the work of Rolston’s longtime idol, the acclaimed photographer Richard Avedon, who in later years produced deeply psychological portraiture that many people felt was cruel in its unvarnished reality.

“The linking that became clear to me after years of studying Avedon’s later work is that that which is gorgeous and that which is grotesque are really the same thing,” he said. “They’re two sides of the same coin.”

Exploring the Duality

For his next project, “Vanitas: The Palermo Portraits”, Rolston continues to deconstruct humanity, exploring what he calls “death anxiety,” something as a celebrity photographer he actively worked to quell.

“The act of using makeup, lighting and sometimes retouching, whatever the tricks are, it all eradicates aging, it all denies death,” he said. “I’m very disturbed by the effects of death anxiety on human culture.”

He traveled to Sicily to take photos of the Christian mummies housed in The Capuchin Catacombs of Palermo. Rolston describes it as an “Expressionist project about death.”

“Vanitas” looks to be Rolston’s most jolting undertaking to date.

“I wanted to celebrate imperfection and the poetry of all that, celebrate age, celebrate weathering, celebrate these things that are rejected in the world of magazines and advertising,” he said. “I’m looking at the same subject matter from a different angle, much more personally and from an older point in my life, a (hopefully) more mature point in my life where I’m more reflective.”

He’s also working on a book, “The Power of Pleasure” based on a master class he teaches at his alma mater ArtCenter focusing on critical thinking and the techniques used in fashion, beauty, and luxury communication.

Rolston Rolls Up Magic in ‘Art People: The Pageant Portraits’

By Andrew Turner

Through the decades, people have flocked to Laguna Beach to witness for themselves the alluring tableaux vivants of Pageant of the Masters. The ‘living picture’ show, around since 1933, has captivated many, serving as an introduction to art for some, including one celebrated photographer who was so consumed by the show that he sought to incorporate it into his own work.

Matthew Rolston, a noted celebrity and fine art photographer who has worked with some of the biggest names in Hollywood, said he first went to Pageant of the Masters when he was a mere 8 years old. He has now seen the show dozens of times.

A passion for art had been awakened within Rolston through family visits to Pageant of the Masters and San Marino’s Huntington Library as a child. In 2014, he returned to Laguna Beach to take in the show with friends. He had been searching for a subject for a passion project; he wanted to create a fine art portrait series that dealt with a question that was bothering him: why are people compelled to make art? In the pageant’s living picture show, he found what he was looking for.

“A passion for art had been awakened within Rolston through family visits to Pageant of the Masters and San Marino’s Huntington Library as a child. ”

“Almost everything in the human experience is imagined,” Rolston said. “We have this amazing thing called imagination that we can then make real. We can imagine something and then realize it. That’s rather amazing.”

Rolston poured his efforts into gaining access to the volunteers in Pageant of the Masters, and he got his chance in 2015 when he took on an assignment with the Wall Street Journal. Following that initial contact, he then received permission to follow through with his own project in 2016, and the culmination of that work is now on display at Laguna Art Museum in an exhibition called “Matthew Rolston, Art People: The Pageant Portraits.”

Rolston’s portraits focus on the volunteer actors that appear in the tableau vivant show who portray the artworks, and solely on them, removing the actors from the context of their performance settings onstage.

““It seems to me that the power of Matthew’s work isn’t in the technique; it’s in the humanity, and anyone can relate to that. ”

“Although I can recognize total mastery when I see it, I’m certainly no expert in the technicalities of photography,” said Dr. Malcom Warner, the museum’s former executive director and curator of the exhibition. “But it seems to me that the power of Matthew’s work isn’t in the technique; it’s in the humanity, and anyone can relate to that.”

Peter Blake, a member of the Laguna Beach City Council who himself is the owner of a prominent city gallery focused on minimalism, said that he was surprised to find himself fixated on the portraits days after he viewed Rolston’s work for the first time. Blake added that in his opinion the quality of fine art is dependent on the artist’s will and commitment to the intent of their work. He found that Rolston’s portraits were powerful for that reason.

“The only difference between commercial art, graphic art, fine art, is that the fine artist is going to a studio in the morning, and they are making exactly what they want,” Blake said. “They don’t care about you. They don’t care about me. They don’t care about the critics, the curators, the collectors or anybody.

“They are literally expressing themselves in the only way they know how, and there is no other option.”